Your company is built on top of a monolith. This monolith is probably your best asset, as your business knowledge is spread inside, however it's also dirty of years of technical debt and teams pushing code without communication between them.

Your monolith is slow, opaque, error prone, not tested. Your developers and sysops teams are afraid of releasing new code, so they end up building and defining heavy process and long release cycles with long manual testing processes. It's because we need to release new versions safely, we can't break production, because recovery or rollback is difficult.

However, the monolith is still there, generating most of your revenue, but also chokes teams performance. How do you improve your main revenue source and also optimize teams for long-term predictability and evolution of your business? Here is where DDD comes in handy.

But before going to DDD (sorry for that 😊) we need to understand why the monolith is still working and serving huge amounts of traffic. Because monoliths are not a wrong software blueprint per se, the issue is with Big Balls of Mud. So let's start talking about monoliths.

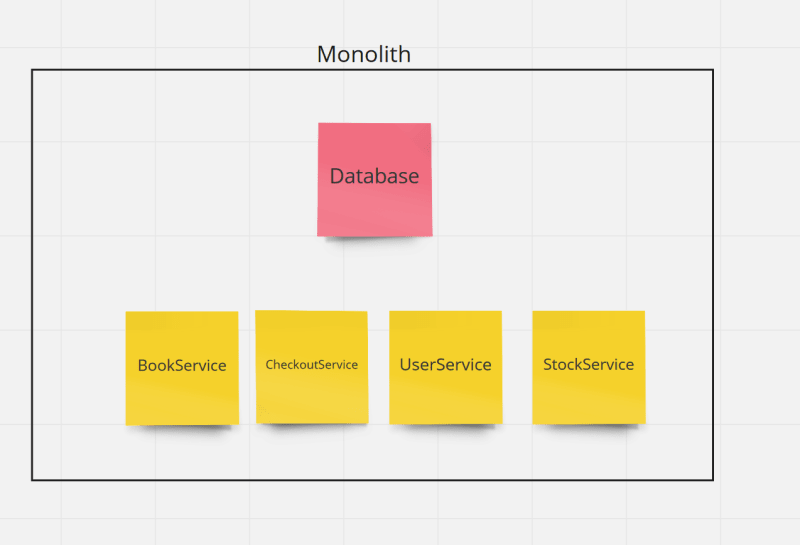

Monoliths are extremely cheap and versatile. The reason why monoliths stand for a long time is because decisions made in a monolith are in the mid-term revertible. Because data and code are in one place, refactors are simpler (can be done with your favorite IDE) and data transfer is cheap. For example, let's start with the following use case:

We are an online shopping platform, like Amazon, and we sell books. During the first iteration of our product, we are not validating the stock of our books in the warehouse because we don't receive that much quantity of purchase orders, so we can fix broken orders manually. We end up with the following architectural diagram.

Few months later, our business starts to grow, we start having a few orders per minute and we have a peak of orders during Black Friday and Christmas. We are not able to handle the increasing number of broken orders because our books are out of stock. We decide to implement a StockService that will validate that the books that we want to purchase have still stock during the checkout process.

As you can see, adding a new service and business rule was quite cheap: just adding a few new classes and a dependency to other services was enough. We didn't take a hard decision, we just followed the pattern that was already in the monolith. We could do that because:

- Moving data in a monolith is cheap

- Decisions in a monolith are limited to a single process

- Monoliths have explicit and common patterns

- Monoliths can be refactored using the help from the IDE

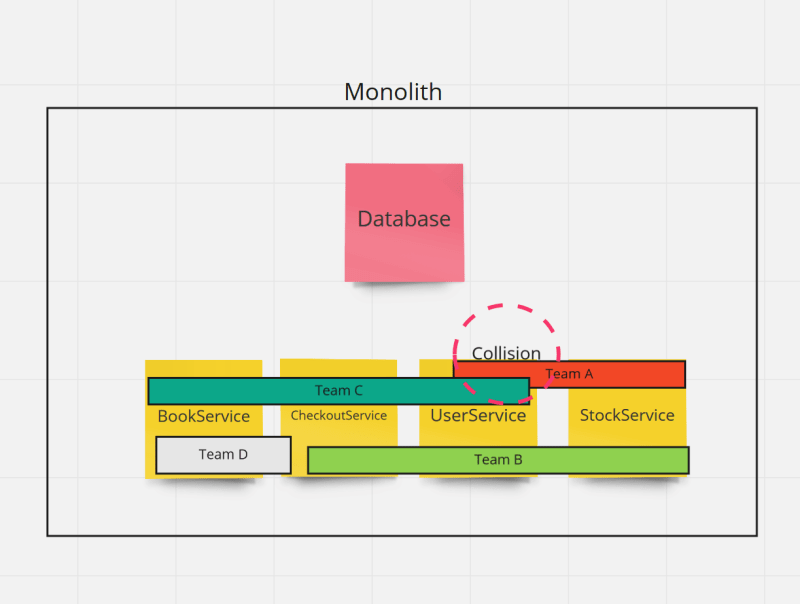

So what we are doing is pushing forward, not taking a complex design decision and delivering new features growing the technical debt. This allows small teams to iterate fast over a product, however it's a problem when the number of teams grow. The reason is because different teams will need data and logic from different services to fulfill user needs.

As you can see there is an overlap between Team A and Team C on the UserService, as they both need data from their users to guarantee that the functionality. There are three common ways to face this situation, split in the following table in three categories: Onwnership, collaboration and effect.

| Ownership | Collaboration | Effect |

|---|---|---|

| One of the teams owns UserService | When the other team requires functionality, asks the owner team | Slows down teams as they have a shared backlog of work |

| One of the teams owns UserService | When the other team requires functionality, makes a PR | Slows down the team that writes the PR because depends of the other team to review functionality |

| Shared ownership | Requires rutinary communication and collaboration to implement new features | Slows down teams because they have a shared backlog |

Because there is no simple solution to this problem, the solution is to split the monolith. To understand the complexity of having different teams on the same code, just take as a reference the complexity of having two threads working with the same set of hundreds of variables in memory.

So we split the monolith into services, after several months or years of work. The most common approach I've seen to split monoliths is the strategy of defining data boundaries. For example, all data related to users will end up in a UserService, the stock information in the StockService and so on.

The problem with this approach is that:

- It might look like Domain Driven Design, but it's not, because it's based on data, not on business knowledge.

- It might look like a microservices architecture, but it's not, because services are highly coupled between them so neither services nor teams are autonomous.

And we built a distributed monolith, which doesn't benefit of moving data easily and is not capable to refactor with the IDE, also being more expensive in infrastructure costs. So how do we make sure that we don't arrive to that situation?

The most basic advice I would do is to split your achitecture based on knowledge, not on data. How a company structures knowledge depends entirely on the people and the business they are on, but there are several patterns to try that are cheap to explore.

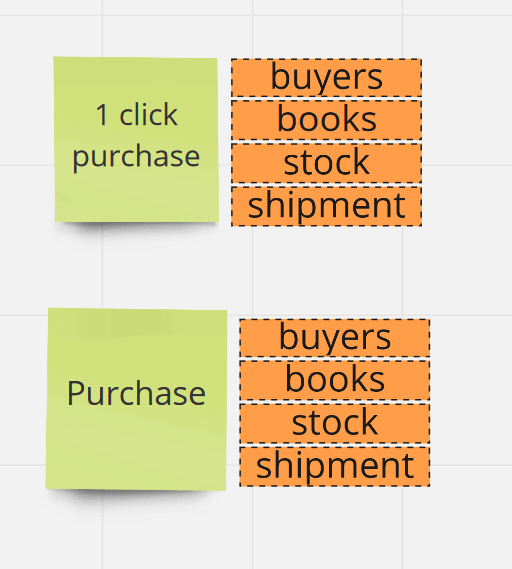

To apply those patterns, we need to think in our business as a business platform: we don't have a product, we have a set of products. Those products are a set of features that apply to a persona. For example, based on this pattern, we can define our shopping platform like in the following diagram:

Each of the product success should be measured and evolved independently. However, as you noticed, there might be dependencies to some cross-product modules. For example, the 1 click purchase might depend on the stock and user information, like the ordinary purchase product. How do we make sure that those dependencies do not affect team performance and we do not duplicate logic?

First, we need to slice the product in modules to understand where the coupling might be happening:

As you can see, both 1 click purchase and Purchase require information from the same sources. However, if we go deeper we can will see differences:

- Are the buyers that are going to use the

1 click purchaseandstandard purchasethe same? - The information that we need about books is the same in both processes?

- Is the information of the stock relevant in the same way in both products?

- Is the shipment information used the same way in both products?

If those questions are yes, what we are probably building is the same product twice, so most probable some of them are at least no, they are different. Let's take a closer look:

| Data Source | 1 click purchase | Purchase |

|---|---|---|

| Buyers | Only people who already bought before other books | Everyone |

| Books | We need all possible info | We need all possible info |

| Stock | We only need to know if we have enough stock | We need to know when the stock is low to push the user to buy |

| Shipment | Only home shipping | Home shipping and delivery companies |

In our case, only Books share the same traits, and they are not behaviour but data. This situation means that our products are bounded contexts where knowledge and understanding of user problems is different. And it makes sense because we are linking knowledge to products, and products to personas.

When we are sharing information between bounded contexts, we should, whenever is possible, favor team performance. This means that sometimes we need to duplicate knowledge. This is quite common in other systems: we have sinks both in the bathroom and in the kitchen. There are different ways to share data across bounded contexts, I personally prefer data streaming with an event based architecture (like SQS) or with an data streaming platform (like Kafka, doing state sourcing). You can also share information with more simple tools like database views (if you have a distributed database like Yugabyte or a AWS RDS).

And even if those kind of patterns seem wasteful, consider a moment how our body works. Our body is piping blood always to our muscles and organs to guarantee availability and health. Consider now if, in your body, every time a muscle wants to move, needs to ask to your heart some blood, and in consequence your heart needs to ask for oxygen to your lungs. Now repeat every second, per muscle.

However, the information needs to come from other bounded contexts (for example, registration processes for new buyers) and they need owners. We can lather, rinse and repeat and split more products until we have smaller modules that are easier to handle for our teams. For example, the following diagram shows product and dependencies on an imaginary book shopping platform:

If we find that most of the related information is exposed to other products (for example, it could happen that all information exposed in Express Sign Up and Profile Sign Up is read in other products, the same way) we can centralise the product to a more generic (generic for personas, not for businesses) and expose a simpler service (like a UserService).

So, to summarize, I would like to share some points that I think are useful:

- Thinking in platforms allows us to split our business better.

- Linking products to personas and also to bounded contexts makes boundaries explicit.

- State-sourcing and event-driven architectures are essential for building distributed and available platforms.

- Teams should not share code, but a common platform.

Thanks for reading!